By Marlene Heloise Oeffinger Dec 5 2013

The woman’s eyes are shining with confusion and embarrassment as the security guard moves her along. Whispers follow them. Two police officers await them at the exit. Their stance is threatening. “Madame, “ one says, harshly, “if you want to receive service, you need to remove your headscarf.” Eyes now downcast, the woman shakes her head. “Then you need to leave or we’ll arrest you“, he continues. “You cannot show up here like this, wearing a headscarf“, he sneers, ”Next time dress differently, like normal people.”

Could scenarios like this soon become reality? In Belgium and France, where wearing religious symbols has been outlawed in schools and public places, they already have. With the vote on Québec’s Charter of Values on the horizon, we have to ask: what are its consequences? Many view the Charter as a legislation that would ensure religious neutrality by the state and its employees as well as greater gender equality. But is that all there is to it?

Bill 60, or the Québec Charter of Values, has been in the media for several months now. The hearings are under way and advocates and critics alike are debating it heatedly. But do we truly know what living under the Charter would entail? Would scenarios like the one above become a daily occurrence? Despite many discussion panels, press conferences and now hearings, the exact content and consequences of the Charter are still shrouded in countless opposing notions, opinions and partial truths. With the help of two experts in Québec’s culture, religion and politics, this article aims to lift the veil on the Charter; to shed light on what lies between the pages of Bill 60 and its consequences for everyday life of Québec’s citizens and its society.

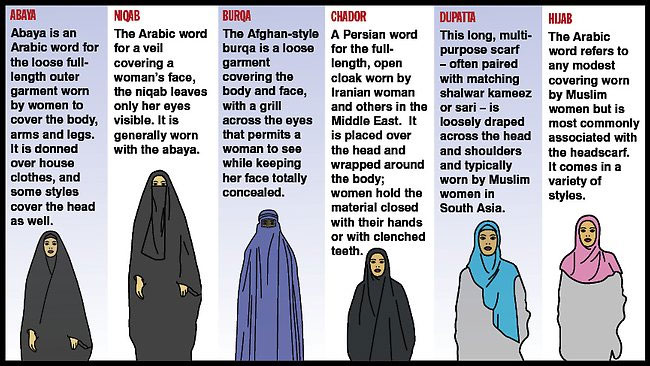

Some of the biggest proponents of Bill 60 are Les Janettes, a group of twenty well-known Québecoise women activists gathered behind the author Janette Bertrand. In a letter to the press, Les Janettes supported the Charter based on the opinion that it promotes secularism thus bringing about greater gender equality, especially in Muslim communities where many women still wear the hijab (headscarf) or niqab (face veil), which the group views as a sign of oppression. One Janettes, Dr. Louise Mailloux, a professor of philosophy at Cégep du Vieux Montréal and well-known writer, is a strong advocate of secularism and feminism. She believes that the bill is crucial to curb the intrusion of religion in the public sphere. “The state is embodied through its employees [who] must reflect its [religious] neutrality.” She also believes, however, that “users [of the state] can wear their religious symbols […].” Yet this is not true. Which clearly highlights one problem surrounding Bill 60; that even its advocates don’t actually know what’s hidden between its pages.

A scarcely discussed point is the fact that not only would the Charter prohibit public service employees to wear religious symbols, but also, more importantly, individuals seeking public service. Which, in simple terms, means a Muslim woman renewing her driver’s license at the SAAQ would have to either remove her headscarf or be refused service. The same is true for a member of the Hasidic community wearing a Kippah, or a Sikh wearing a turban. And let’s not forget that public services include anything from applying for your driver’s license or your RAMQ card, to receiving medical treatment and education.

While Les Janettes believe the Charter will bring greater equality and freedoms, especially for Muslim women, many opponents of the Charter disagree, believing that the exact opposite will happen. Many inroads have been made in the past decades for the integration of Muslim women into Québec society; they hold different kinds of professions, including in the public service sector, and many are seeking higher education. Bill 60 could reverse all that.

But Mailloux argues this worry is “emotional blackmail”. “We must stop infantilizing and victimize veiled women. They will have to make a choice.” She also points out that similar arguments were made in 2004 when France banned the wearing of conspicuous religious symbols for high school students. “Finally, the fallout did not happen,” she reasons, “the girls removed their veils and remained in public school”. The statistics, however, speak differently. Young girls being expelled from school for refusing to remove their hijab is now a common occurrence in France.

Banning children from school was just one aspect of France’s tough road to enforced secularism. Since the introduction of the ‘burqa ban’ in 2010, Muslim women have faced a lot of hostility. Those wearing the niqab openly have been arrested and fined on numerous occasions. They have also been confronted with a rise in extremism – physically assaults, even in broad daylight, without interference. Many of these women are scared to leave their houses and it has certainly curbed their public involvement and integration into society.

Banning children from school was just one aspect of France’s tough road to enforced secularism. Since the introduction of the ‘burqa ban’ in 2010, Muslim women have faced a lot of hostility. Those wearing the niqab openly have been arrested and fined on numerous occasions. They have also been confronted with a rise in extremism – physically assaults, even in broad daylight, without interference. Many of these women are scared to leave their houses and it has certainly curbed their public involvement and integration into society.

Dr. Daniel Salée, a professor at Concordia University, whose research focuses on the politics of ethnicity and citizenship in Québec, sees the Charter as a “throwback to the old days”. “We have made a lot of inroads with respect to social justice and we are fairly open, more so than Europe. And now, we are backtracking.” He worries that what happens in France could also happen in Quebec. But in fact, it already has. There have been twenty-one reported cases of assault against Muslim women, even before the Charter has been signed into law.

“It’s the moral panic of the white man in Western liberal democracies to lose control that’s at work here.“ Dr. Salée believes that our Judeo-Christian based cultures feel threatened by the ‘barbaric’ ones of [the] immigrants. “We want them [to] take on our values, leave theirs at the door.” He feels it’s a remnant of colonialism, which is still ingrained into our thinking and society, and stems from an identity crisis within the Quebec francophone culture. “Here in Québec,“ Salée says, “it’s of course the constant worry that immigrants, their values and religious practices undermine the our culture.” So is enforcing values under a mantle of secularism that will most likely marginalize large parts of Québec’s society really the way to go?

“It’s a smokescreen and they hijacked secularism. If you are against the Charter than you are against secularism.”Dr. Salée maintains that Bill 60 is not what secularism is about. And with that he raises an important point. Secularism is defined as the principle of separating the persons mandated to represent the State from church. It refers to the view that human activities and decisions, especially political ones, should be unbiased by religious influence. It also asserts freedom from governmental imposition of religion, religious teachings, and on religious matters. Based on that, institution of the Charter seems the opposite of secular.

Dr. Louise Mailloux strongly disagrees. “Secularism concerns political and legal relationship between the state and religions. It is therefore the responsibility of the State to legislate secularism.” She believes that for a State to be neutral in religious terms, it is necessary that it create a distance to religions. “In 2005, the Government of Québec adopted Bill 95, which […] put an end to religious instruction in public schools. Surprisingly, that time no one accused the government of dictatorship“, she says. For many people, however, the separation of government and church has already happened a long time ago, in the 1960s. Like Dr. Salée, they believe it’s not an issue anymore. In fact, he argues that if the State wants to be truly secular, it should stop subsidizing religious private schools. “Government finances ~ 60% of their budget. [That is] not secular.“

So where do we draw the line in the quest for Québec’s secularism? For Dr. Mailloux, there is no line. “Religious freedom […] is not an elastic concept“, she says. “Just as freedom of expression is limited by the prohibition of hate speech, religious freedom can find its limit in the ban of conspicuous religious signs.” But therein lies the crux. What are conspicuous religious signs? The headscarf of a non-Muslim professor at Concordia University? The oversized cross dangling from a teenager’s neck? What about the full beards fashionable amongst many men today? Conspicuous religious signs or fashion trends?

Dr. Salée’s thinks that regardless of whether the Charter becomes law or not, it has already divided our society deeply. And that it will do so even further alienating entire cultural groups, discriminating their values and heritage. “It will be even more than that. You will create pockets of society where these people have no full access to their rights of citizenship.”

To some, the Charter may feel like repeating the mistakes of the past. Does it really matter whether the State ‘belief’ is called Catholicism or Secularism if it discriminates a part of its citizens? For regardless of whether it’s under the mantel of religion, language, culture, race, secularism or values, all it ever leads to is the alienation, segregation and persecution of a part of society. Which begs the final question: Have we, as a modern society of European origins, not learned from several hundred years of religious persecutions that spanned European history? Especially given the fact that many who settled this continent were themselves fleeing from religious or economical oppression? As Dr. Salée puts it: ”When your state starts creating categories of people, saying that some categories are better than others, the ones […] in its good categories will feel above anybody else. That’s what happened in Germany and Austria in the 1930s, what is happening in France, Belgium, and even here, now.”

Pingback: Marlene Heloise Oeffinger